Is religion an antidote to social media’s ills?

We are more connected than ever and yet deeply unmoored.

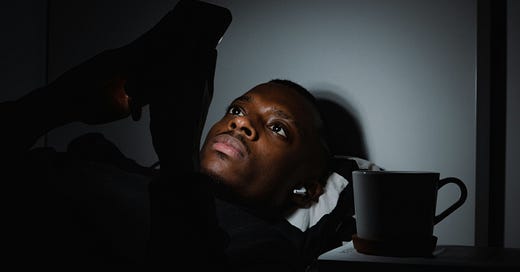

Whenever I’ve spent a lot of time scrolling through social media, I’ve usually felt worse afterwards. I understand not everyone might feel this way. Some people derive a twisted satisfaction from being very online. Others are blissfully offline or occasionally lurk.

But I’ve talked to plenty of people who share a similar sense of dread. They feel obligated, for professional or social reasons, to maintain an online presence, but don’t want to be consumed by comparison traps, rage, or despair. They’d rather not waste countless hours using addictive technologies. For all the good produced—the affinity groups fostered, the breadth of information transferred—the rise of social media has coincided with a decline in meaningful face-to-face relationships and communities. We are more connected than ever and yet deeply unmoored.

By now, there is plenty of research demonstrating the detrimental effects of social media use. It’s gotten to the point that there are serious conversations taking place among policymakers about regulating these technologies. Earlier this week, Vivek Murthy, the surgeon general of the United States, called for a warning label to be placed on social media platforms, one which states that social media is associated with “significant mental health harms for adolescents.” He also recommended that schools create “phone-free experiences” and that parents withhold social media access from their kids until after middle school.

The surgeon general’s call for a warning label on social media comes after his previous warnings concerning the nation’s “epidemic of loneliness and isolation.” Social disconnection has been shown to increase the risk of heart disease, dementia, and stroke. One study has compared the risk effects of loneliness and isolation to smoking 15 cigarettes a day.

In this landscape, it’s been interesting to observe nonreligious writers lament the decline of organized religion. Derek Thompson at The Atlantic wrote an article, “The True Cost of the Churchgoing Bust,” about how he—as an agnostic—had previously applauded the decline of faith in America. But now he’s worried that the loss of religion has exacerbated destabilizing forces such as hyper-individualism.

This worry is merited. According to a recent Pew study, people who are religiously unaffiliated are, on average, “less likely to vote, less likely to have volunteered lately, less satisfied with their local communities and less satisfied with their social lives.”

Jessica Grose at The New York Times has written an in-depth series about Americans moving away from religion. Grose identifies as Jewish but nonobservant. While she isn’t fond of religious rituals, she’s felt conflicted about what to pass down to her children. Her series sympathetically airs all the good reasons people have for leaving some form of religion. Yet, in concluding her series, Grose can’t help but acknowledge religion’s power to create supportive communities. She writes,

I asked every sociologist I interviewed whether communities created around secular activities outside of houses of worship could give the same level of wraparound support that churches, temples and mosques are able to offer. Nearly across the board, the answer was no.

It seems that an uninhibited approach to social media is worsening the forms of loneliness and isolation that religion is uniquely suited to address.

While paraphrasing Jonathan Haidt’s work in The Anxious Generation, Thompson shows that it’s helpful to compare digital life and religious rituals in terms of how they impact us. He breaks it down as follows.

Digital life is:

Disembodied

Asynchronous

Shallow

Solitary

Religious ritual is typically:

Embodied

Synchronous

Deep

Collective

Saying prayers, meditating, discussing readings, singings songs together in a community of ongoing relationships meets the social needs of our species in a way that plugging into a feed of constantly churning content never will.

What’s relevant here is less religion as simply a set of metaphysical beliefs but as participation in community and ritual. The Pew study I previously cited also mentions this: “…it’s not whether a person identifies with a religion (or not) but whether they actively take part in a religious community that best predicts their level of civic engagement.”

If social media isn’t going away, would it help to anchor ourselves in something tangible that can make us feel better by connecting us to others and a higher purpose?

Obviously, organized religion has plenty of its own problems. One can easily point out toxic and abusive communities, or spot the demagogues and followers who use it to galvanize patriarchy, racism, and hatred of others. Religion isn’t a silver bullet. But to cede it entirely to extremists would be to give up an invaluable tool at a time when we might need it the most.